Hail To Thee, Blithe Spirit!

2nd July 2021 marks the 80th anniversary of the original production of probably Coward’s most popular play, Blithe Spirit. This week, we look back at its original life on stage and its continued ‘afterlife’…

Portmeirion, Wales. 1941: Coward has escaped London and the Nazi bombs of the Blitz to take a break in the seaside resort of Portmeirion with Joyce Carey. It was during this break that he wrote – very quickly – the first draft of Blithe Spirit; the play which would become not only his most popular play but one of the most enduring stage works of the 20th Century.

The title of the play is taken from Shelley's poem "To a Skylark", ("Hail to thee, blithe Spirit! / Bird thou never wert"). As Coward later recalled,

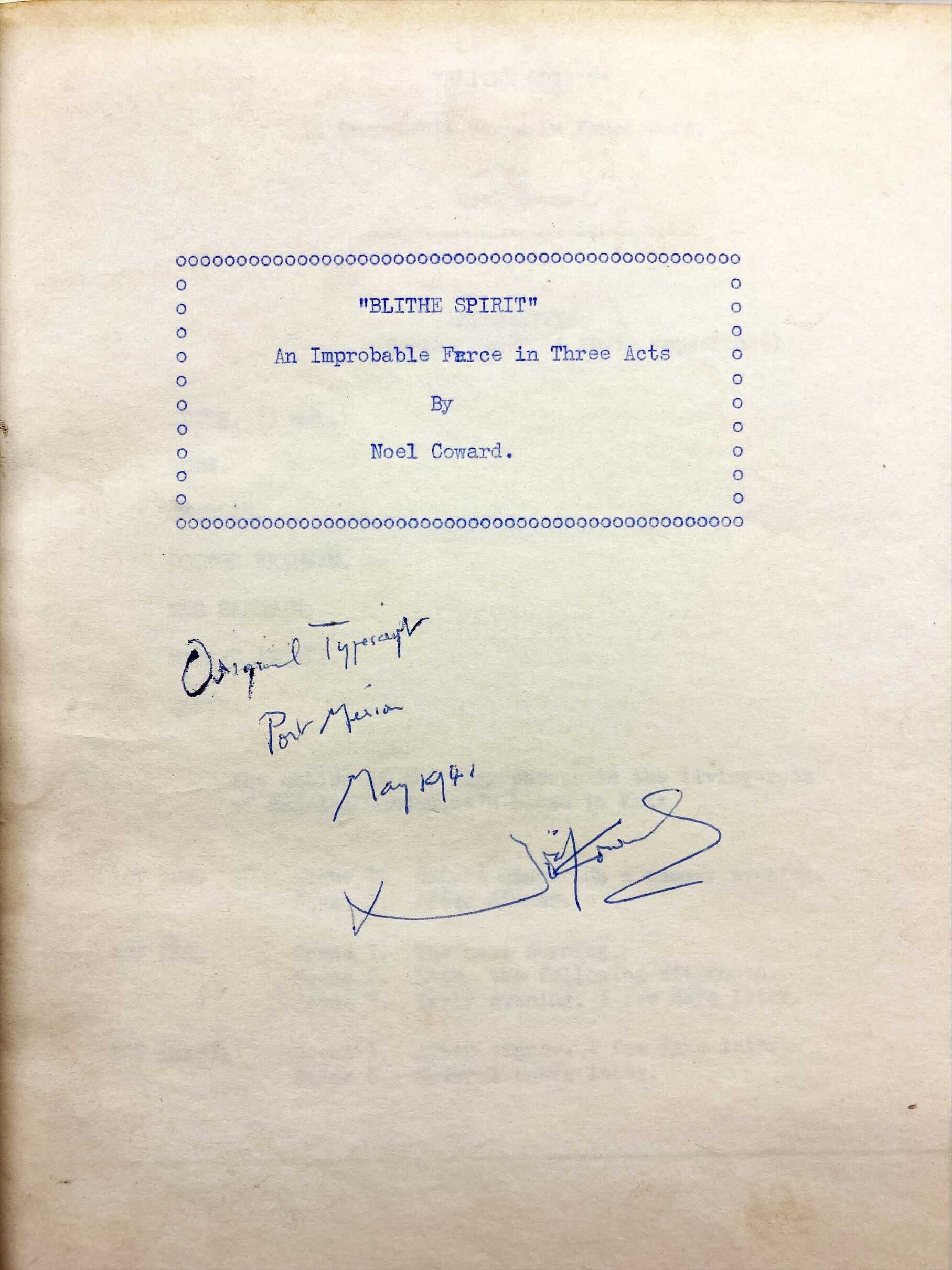

Coward’s own original typescript (Noël Coward Archive Trust)

“We sat on the beach with our backs against the sea wall and discussed my idea exclusively for several hours … By lunchtime the title had emerged together with the names of the characters, and a rough, very rough, outline of the plot. At seven-thirty the next morning I sat, with the usual nervous palpitations, at my typewriter …The table wobbled and I had to put a wedge under one of its legs. I smoked several cigarettes in rapid succession, staring gloomily out of the window at the tide running out. I fixed the paper into the machine and started. Blithe Spirit. A Light Comedy in Three Acts. For six days I worked from eight to one each morning and from two to seven each afternoon. On Friday evening, May ninth, the play was finished and, disdaining archness and false modesty, I will admit that I knew it was witty, I knew it was well constructed, and I also knew that it would be a success.”

This draft remained almost entirely unchanged when it went into rehearsal a couple of months later (though he did make some revealing changes which I’ll come to later).

The Manchester Guardian thought it "not untouched by genius of a sort”. Similarly, The Times considered the piece the equal not only of Coward's earlier success Hay Fever but of Wilde's classic comedy The Importance of Being Earnest.

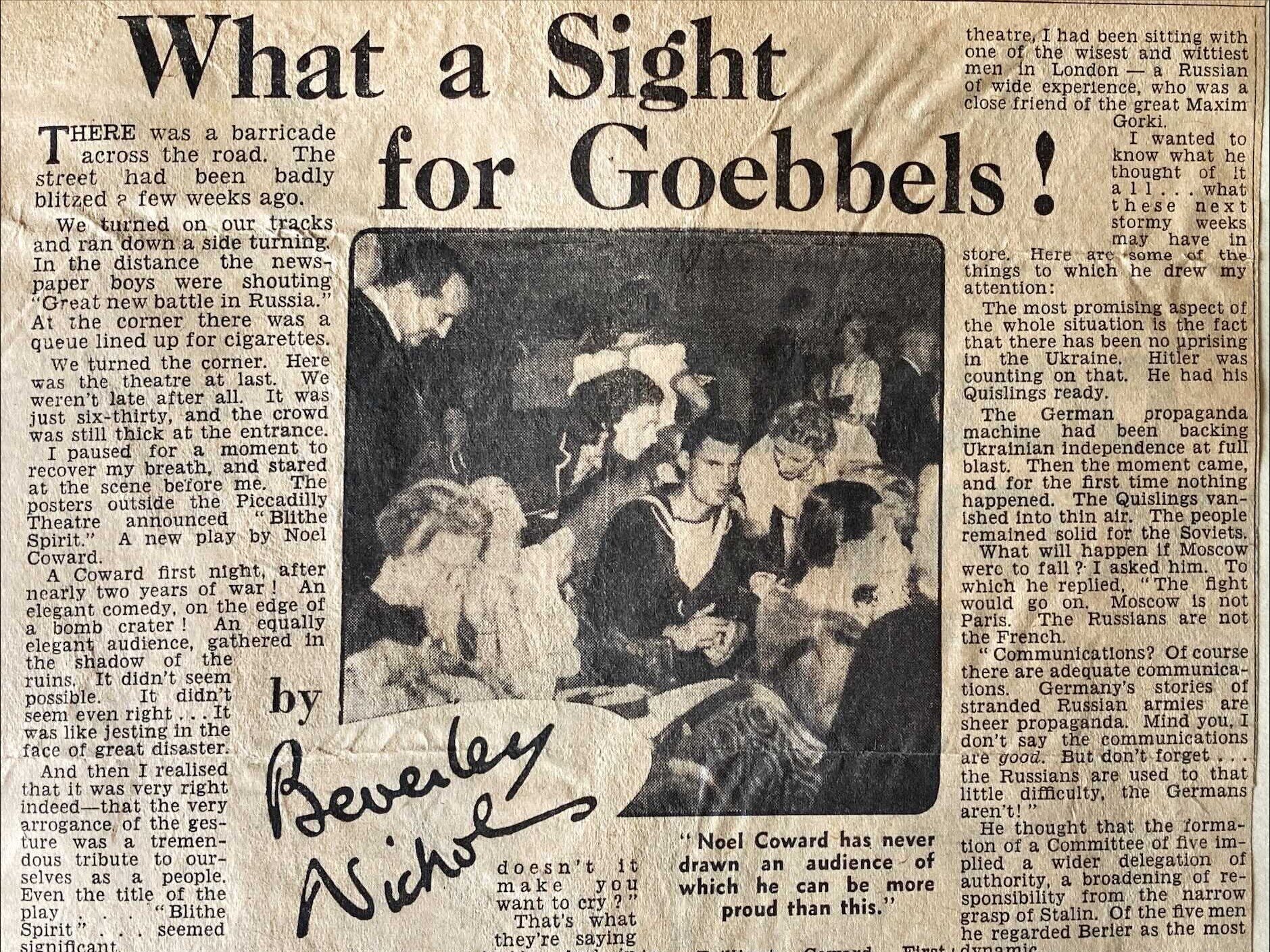

There were some reservations about the propriety of treating death so lightly, especially in the midst of a war: "London received Mr Noël Coward's ghoulish farce with loud, though not quite unanimous acclaim. There was a solitary boo – from an annoyed spiritualist, presumably." (The Guardian) but most agreed with The Daily Herald that it was a “superb, sophisticated escape from the realities of today”.

Article by friend Beverley Nichols from Coward’s personal scrapbook (Noël Coward Archive Trust)

As Brad Rosenstein, curator of the Noël Coward: Art & Style exhibition notes, “Death was an imminent possibility for every member of the audience. That Coward could touch such a potent immediate nerve and transform it into delightful entertainment is a vivid demonstration of what a truly daring playwright he was. People desperately needed to laugh, and the play is hilariously funny. For its first audiences, just the act of dressing up and going to the theatre through the devastation and rubble, risking your life for a good laugh, must have seemed like an act of patriotic defiance. The play is set in pre-war days, so represents a time of ease and elegance (even ghostly Elvira wore an exquisite Molyneux gown!) that even then must already have seemed richly nostalgic to an audience enduring rationing and air raid shelters.”

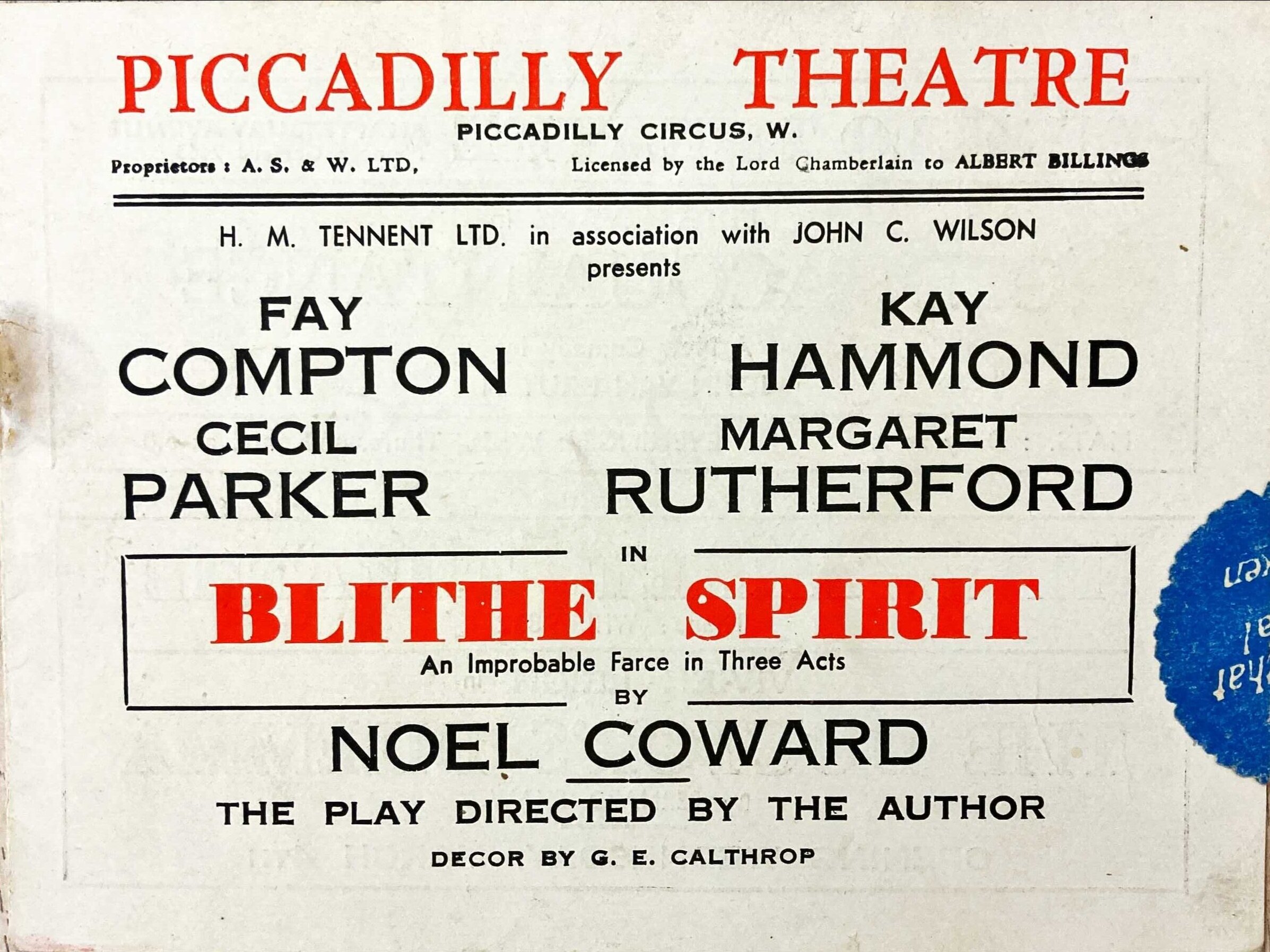

Singled out for high praise at Press Night was Margaret Rutherford in the role of Madame Arcati: "…here is a new play, a gay play, and one irresistibly propelled into our welcoming hearts by Miss Rutherford's Lady of the Trances, as rapt a servant of the séance as ever had spirits on tap." Clearly in The Observer’s mind, the play’s success was due to Rutherford’s performance.

For a closer look at Rutherford as Arcati, go to Part 3 of this series: Arcati… Always.

Surprisingly, Coward didn’t like Rutherford’s performance, and was somewhat frustrated by her popularity with audiences. For both press and public, Rutherford stole – even made – the show. But not for Coward. Writing to Jack Wilson (who was to direct the Broadway production), he wrote:

“The great disappointment is Margaret Rutherford, whom the audiences love, because the part is so good, but who is actually very very bad indeed. She is indistinct, fussy and, beyond her personality, has no technical knowledge or resources at all. She merely fumbles and gasps and drops things and throws many of my best lines down the drain”

Coward had always insisted the character should be played with ‘matter-of-factness’ who should take herself very seriously.

Stage Manager’s edits to the ‘prompt script’ for the original production (Geoffrey Johnson Collection, Noël Coward Archive Trust)

“She’s the most sincere person in the play.” says Professor Russell Jackson, Emeritus Professor of Drama at Birmingham University, “The way she talks to and about the people who have ‘passed over’ is affectionate and the humour often comes from her treating them as normal however famous (or infamous) they may have been.”

It is perhaps for this same reason that prior to rehearsals, Coward trimmed some of her less serious lines, such as:

“Madame Arcati: I have never had a husband Mrs Condomine. Madame Arcati is merely a nom de plume as you might say. My real name is Gladys Stephens.”

Notably, when the production was transferred to Broadway, Arcati was played by Mildred Natwick, who Coward felt was closer to his vision for the character. She would also play the role on CBS TV alongside Lauren Bacall as Elvira.

Another change was made for external reasons. The reference in the script to the death of “old Mrs Leggatt” had to be removed when Coward read the news of the high profile death of Lord Monkton’s secretary in a plane crash. Her name: Shelagh Leggatt. The script was immediately changed to say ‘Mrs Plummet’ (Coward’s idea of a dark joke?).

Original Programme (NCAT)

The original production of Blithe Spirit would run for 1,997 performances, change theatres twice and go on a national tour. The run set a record for non-musical plays in the West End that was only surpassed by The Mousetrap in 1957.

At certain points during the run, and on tour, the role of Charles Condomine was played by Coward himself (and he would also appear in the CBS TV adaptation) and also by John Gielgud, for one of the wartime ENSA tours. Ever since, both the roles of Charles and Madame Arcati have become star vehicles. For a look at some of the major names who have played Madame Arcati, check out Part 4 of this series: Arcati Through The Ages.

Following the original production, there were not only frequent revivals in the UK and US but also adaptations for TV, radio and film. There was even a musical adaptation and a ballet. More about those in Part 2 of this series: Blithe Spirit: Afterlife.

If you’re interested in learning more about the writing process behind Blithe Spirit, you’ll want to read Professor Russell Jackson’s article in the Spring 2020 issue of Home Chat, copies of which are available to visitors of the Noël Coward Room. To book a visit email cowardoffice@alanbrodie.com.

Book a visit to the Noël Coward: Art & Style Exhibition here